Claire Ellis is a Canadian-born ceramic artist and designer based in Naarm (Melbourne). While working as a chef at one of the world’s best restaurants in Naarm, Attica, Claire began making tableware for the tasting menu and created a ceramics studio within the restaurant. Claire left Attica to focus on ceramics full-time in April 2021.

Tell me a little bit about your childhood, education, and background in terms of how you first became interested in creativity, design, and sustainability.

I grew up alternating between Ottawa and Winnipeg in Canada as part of a creative family. At various points in time, my mom had her own sewing company and worked as an artist using oil pastels. My dad built a lot of interesting things as a hobby. Most memorably, after taking a welding course, he built my younger brother a go-kart out of parts from a treadmill he found at the side of the road. My stepmom is a cellist and my sister studied architecture before becoming an art teacher. After graduating high school, I studied culinary arts and later moved to Australia for more experience. I was shocked by the amount of waste in many restaurants. I ended up at Attica in Melbourne where my informal ceramics studies on my days off alongside my involvement in menu planning meetings led me to create custom tableware for the tasting menu. My experiments using waste materials in ceramics began with eggshells and glass from the restaurant.

How would you describe your project/product?

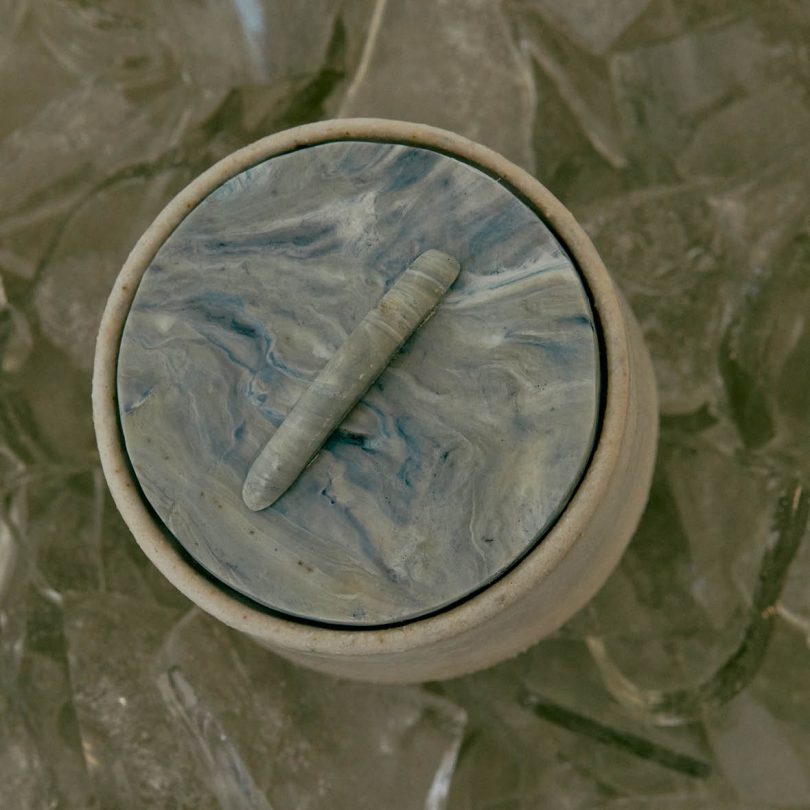

Solace Containers are wheel-thrown recycled clay vessels, glazed using eggshells as the source of calcium, lined with pools of recycled glass and finished with lids made from recycled plastic clay bags. The lids on the minimalist forms feature swirls of color which come from the colored print on the plastic bags which are kneaded, twisted, and stretched like pulled candy before being pressed into sheets.

What inspired this project/product?

Solace Containers were inspired by my experiments using waste in my two workplaces; kitchens and ceramics studios. I wanted to figure out how to use materials available in my environment that would otherwise get thrown away or shipped somewhere else. Partly out of a feeling of responsibility but also because I find it exciting to use local materials that have significance for me. The name of the containers came from my experience with climate grief and my desire to focus on solutions.

What waste (and other) materials are you using, how did you select those particular materials and how do you source them?

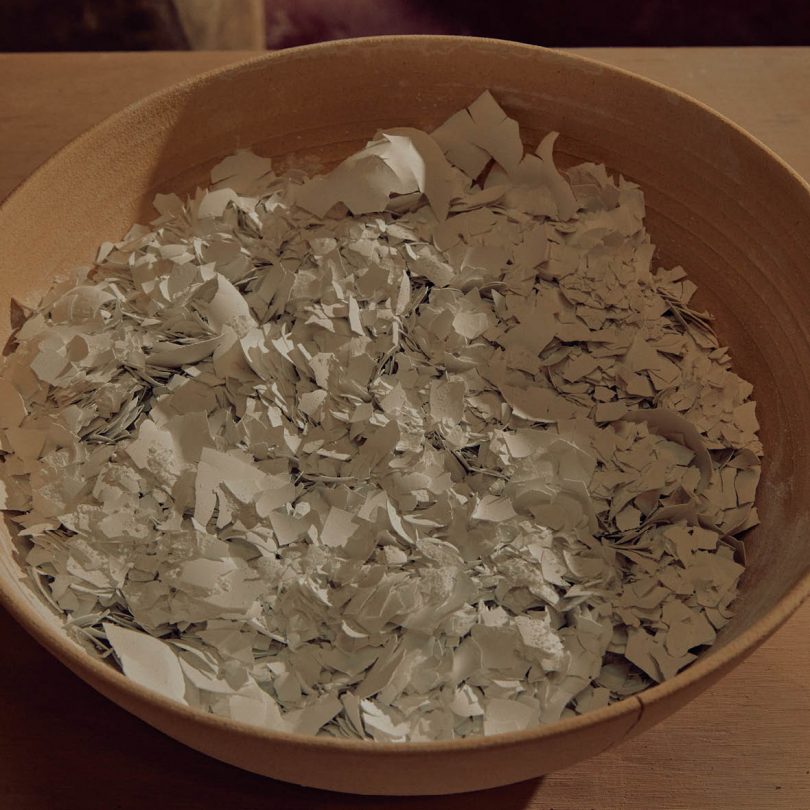

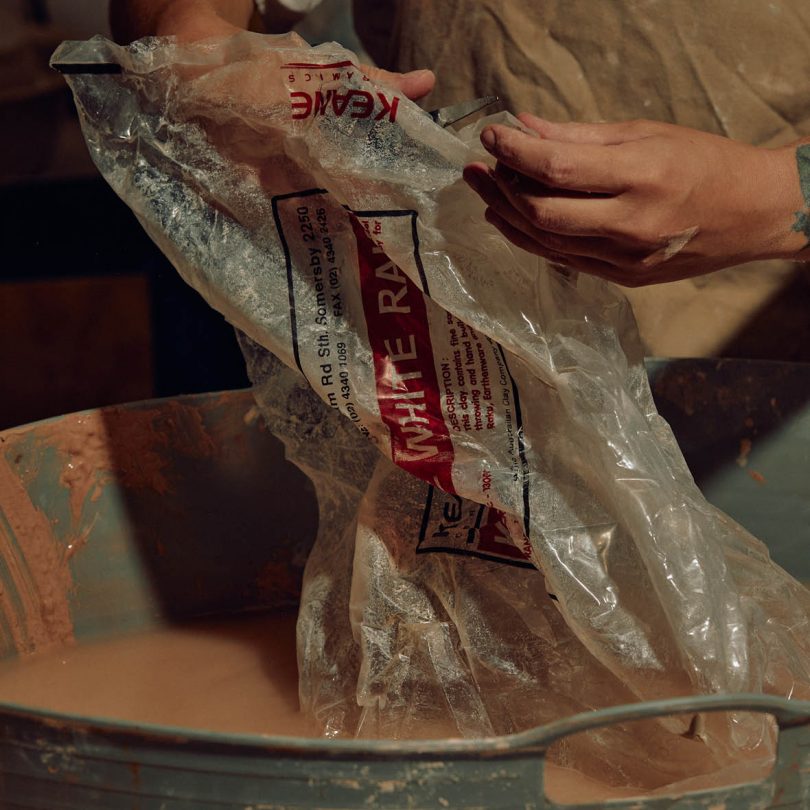

The clay for the containers is reclaimed from my practice. I collect clay bags from my local ceramics community, the plastic adds up quickly and ceramicists are very happy for me to take it. I source wine bottles and eggshells from restaurants. Glass is made of a similar recipe to ceramic glazes and eggshells are calcium carbonate which is the same chemical compound as one of the common (mined) raw materials in glazes. The other glaze materials used for the Solace Containers are talc, kaolin, and nepheline syenite which are all mined derivatives of rocks. With more testing, I intend to replace those virgin materials with waste from other industries.

When did you first become interested in using waste as raw material and what motivated this decision?

The first waste I became interested in using was food waste while I was working in kitchens. I saw bins overflowing with the best produce in the country in some places, but in other places, I saw how awareness and creativity could solve these problems and change the way people looked at off-cuts or by-products. I’m inspired to do the same. In my ceramics practice working with waste requires a lot of extra monotonous and time-consuming physical labor to process the materials, but because the work feels meaningful, I find it easier than doing more straightforward jobs that don’t align with my values.

What processes do the materials have to undergo to become the finished product?

The eggshells are dried, fired in my kiln to purify the calcium carbonate, ground in a pestle and mortar, and then passed through a fine sieve. The glass is smashed with a hammer after the labels have been removed and the shards are placed in the base of the raw-glazed containers before firing. To make the lids, the clay bags are washed and dried and any tape is removed. The labels are then cut off and separated by color. Bundles of the plastic bags are melted in an oven, kneaded, stretched, and twisted before being pressed into sheets. The lids and handles are laser-cut, polished, and attached together.

What happens to your products at the end of their life – can they go back into the circular economy?

I offer repair and recycling services encouraged by discounts for products at the end of their life. The recycled plastic lids can be polished or recycled into new lids. Broken ceramic components can be repaired using Japanese kintsugi methods, and ceramic pieces beyond repair can be crushed into grog that I use to make clocks.

How did you feel the first time you saw the transformation from waste material to product/prototype?

I was so excited. I didn’t know if any of my material tests would end up being successful. In particular, the tests with eggshells and plastic took a lot of tweaking and troubleshooting which made it so rewarding when I saw everything come together for the first time. The Solace Containers have come about from slowly putting together pieces of a puzzle one by one. Finding each piece has been a thrill.

How have people reacted to this project?

When people see the Solace Containers for the first time, they’re surprised about the materials and curious about the processes. They expect the lids to be made of resin or stone. I’ve had some really encouraging responses, especially from other ceramicists who are grateful and delighted to see something creative being done with the clay bags. A bonus for me has been meeting other makers through the bag collections, which have turned into a lovely community-building opportunity.

How do you feel opinions towards waste as a raw material are changing?

I think opinions are changing a lot through conversations that suggest that we find a better word for waste and what that implies, for example your thought-provoking podcast episode with Seetal Solanki. It’s exciting to imagine a time when we all see waste as a resource and it gets called something else because we stop wasting it. Hopefully, we get to that place quickly.

What do you think the future holds for waste as a raw material?

I think waste will eventually get a name change and will become a more mainstream material. I think there will be regulations in the future on using unsustainable raw materials and it will become the norm to use waste or biodegradable materials. I think younger generations especially will focus more on solving these problems and over time recycling and upcycling will keep getting easier, more efficient are more accessible. I also think there will be more BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ people in leadership positions who will accelerate positive change in this space.

Katie Treggiden is a purpose-driven journalist, author and, podcaster championing a circular approach to design – because Planet Earth needs better stories. She is also the founder and director of Making Design Circular, a program and membership community for designer-makers who want to join the circular economy. With 20 years’ experience in the creative industries, she regularly contributes to publications such as The Guardian, Crafts Magazine and Monocle24 – as well as being Editor at Large for Design Milk. She is currently exploring the question ‘can craft save the world?’ through an emerging body of work that includes her fifth book, Wasted: When Trash Becomes Treasure (Ludion, 2020), and a podcast, Circular with Katie Treggiden.

You can follow Katie Treggiden on Twitter, Instagram, and Linkedin. Read all of Katie Treggiden’s posts.