Disharee Mathur is a graduate of the MA/MSc Innovation Design Engineering program at the Royal College of Art and Imperial College, London. She received her Bachelor of Fine Arts in Interior Design at the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) and has worked at internationally renowned Interior Architecture firms – Studio O+A (San Francisco, USA) and Gensler (Bangalore, India). Today, she is an interdisciplinary designer working across products, interactions and interiors – and her NewBlue project reimagines damaged sanitary ware into vases and accessories.

Tell me a little bit about your childhood, education and background in terms of how you first became interested in creativity, design and sustainability.

I grew up in Jaipur (India) where hand crafting is part of the daily social fabric and culture – whether it is cooking cuisines crafted with spices or using block-printed textiles across the home. I come from a family of doctors who are also singers, writers and musicians. I used to draw and paint as a child. Later, I started doing still life painting at high school and was mentored by my aunt who is an artist. That was when I learned to observe both things and people closely. My interest in painting led me to design. I secured a scholarship to study at the Savannah College of Art and Design. At SCAD, I was enthralled by the possibilities that creative disciplines offered. I started with animation, learning about creating 3D environments for VFX drew me towards designing spaces, and ultimately I majored in Interior Design. There was a materials library in the department that made me feel like a kid in the candy store! After SCAD, I worked in the industry for a few years and wanted to diversify my scale of work across disciplines. I was interested in applying artistry to principles of strategic design and sustainability. These dots connected at the RCA and Imperial College, during my masters. It was exciting to learn about circularity and find overlaps between my cultural practices & crafts and the western definition of circularity in design – and “making with waste” was also not far from tradition at home – whether it was creating outfits out of my mum’s old saris or my grandma using lemon peels for pickles.

How would you describe your project or product?

NewBlue is a conversation between a traditional pottery craft, material science and design that sheds light on a new perspective on craft preservation and waste management. The project revives an ancient craft practice using ceramic waste as an ingredient in the NewBlue Pottery recipe. The waste is used as a strengthener while keeping the artistry and technique of the Jaipur Blue Pottery craft intact. NewBlue diversifies Blue Pottery beyond pottery, to explore new scales and applications for the craft and their product range into furniture and architecture.

What inspired this project or product?

Conversations with craft communities in Jaipur and the local government’s efforts to find land to accommodate sanitary ware waste. India has the largest concentration of craft in the world yet only 2% of the global handicraft market share. These numbers reflected reality when I started interviewing craft units and communities in my hometown. The Jaipur Blue Pottery craft was studied to understand the scenario from the ground up. While the craft is celebrated for its ornamentation and technique, less than 300 artisans are practicing today. Apart from the low incentive for the next generation to continue the practice, artisans mentioned material deterioration and low material strength as challenges to the development of the craft. This inspired me to focus on material innovation for craft preservation. Using the waste was also an incentive for the craft units to become eligible for state economic opportunities as contributors to local waste management. Recent craft preservation efforts were geared towards preserving practices as artifacts, rather than enterprises in the economy. I was inspired to find an intersection between traditional craft and scientific innovation to seek a contextual solution.

What waste material are you using, how did you select those particular materials and how do you source them?

I am using rejected sanitary ware (sinks and toilets) from local retail stores in Jaipur. Most of these stores have 3-4 rejected pieces in shipment with cracks and defects, that cannot be sold, so end up becoming waste. We use these pieces as a raw material for NewBlue in the Jaipur Blue Pottery workshops – they are used as a strengthening ingredient. These are processed using the existing workshop equipment. We selected this material after over 50 experiments with different waste materials and doing compressive strength and material hardness tests on all fired samples. The samples with the sanitary ware waste showed the best results. The artisans reviewed all the samples and gave feedback along the way. The selection criteria were accessibility of the ingredient logistically and economically while retaining the aesthetics and processes of the traditional craft. Recycling glass is already a part of the ancient recipe so introducing another waste material is not too far from tradition. We source this waste in the same way the artisans source recycled glass from local art-framing stores. The small quantity of the waste required in the recipe allows wider accessibility for sourcing.

When did you first become interested in using waste as raw material and what motivated this decision?

I first became interested in using waste because of its excess and, as a result, its accessibility. After learning more about the quality of ingredients in industrial waste like ceramics, that motivated me to experiment with the material as a potential resource for use. On reflection, it’s also a great tool for prototyping and testing ideas for form and textures.

What processes do the materials have to undergo to become the finished product?

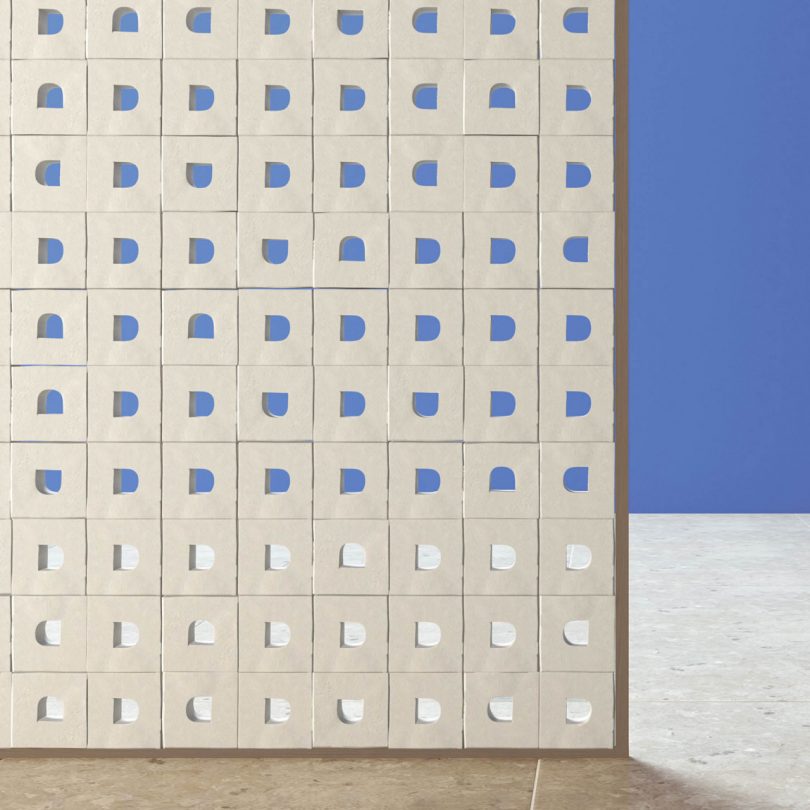

NewBlue material is made with the addition of waste as an ingredient in the traditional Blue Pottery process. Blue Pottery is one of the few pottery techniques in the world that does not use clay. They use locally sourced quartz powder, recycled glass, plant-based gum, and sand as binders ground together and kneaded to make a dough. The dough is then molded like a flatbread, sun-dried, and finished with intricate motifs in oxide pigments as an underglaze. These ceramics are fired only once at low temperatures of 790-800 degrees celsius. The traditional craft practice remains untouched as this material can only be made and used in existing Blue Pottery craft workshops. The NewBlue material variations are named as “A synonym and Antonym for Jaipur Blue Pottery” for this very reason. The Synonym material is synonymous with the craft in color and texture but with doubled strength. It is embodied as an end-table from existing traditional molds, showcasing the newly acquired strength and scale of the material. The Antonym is unglazed and embodied as passive cooling architectural tiles showcasing the material strength with porosity.

What happens to your products at the end of life, can they go back into the circular economy?

The artisans have traditionally experimented with mosaics to find ways to reuse the pieces and these can be broken down again to make smaller pieces to be put back in circularity. However, more robust research is required to make this reach its full potential at the end of life.

How did you feel the first time you saw the transformation from waste material to product /prototype?

It was magical! There were so many happy accidents as we experimented with different types of waste, from terracotta street vendors to a china clay factory. We found new colors and textures which we couldn’t use at the time to be strict with craft compatibility. But I’d love to explore some of those for other pieces!

How have people reacted to this project?

It has been really positive and encouraging so far – and I’d love to take this concept to more remote rural communities that were not able to test this in their workshops due to pandemic restrictions.

How do you feel opinions towards waste as a raw material are changing?

There are different perspectives in the East and the West. Designers in the West are really open to using waste as a resource but are sometimes limited in finding sustainable manufacturing techniques to process it at all times, while the East has strong cultural traditions around using certain types of waste in their practices but is sometimes not open to use all types of waste materials. There is real potential in the two perspectives transcending borders to adopt the ‘waste is wealth’ method of making.

What do you think the future holds for waste as a raw material?

It’s exciting to discover different types of waste as material resources that may further feed into the economy. I am always enamored with how beautifully nature creates and processes waste – dried leaves in autumn are a great example. I hope as designers we are inspired by nature’s processes to feed future circular systems – whether it is material movement or processing what’s left behind after use. The future of using waste material may also draw from past traditional practices of making with local abundance – waste or used materials.

Katie Treggiden is a purpose-driven journalist, author and, podcaster championing a circular approach to design – because Planet Earth needs better stories. She is also the founder and director of Making Design Circular, a program and membership community for designer-makers who want to join the circular economy. With 20 years’ experience in the creative industries, she regularly contributes to publications such as The Guardian, Crafts Magazine and Monocle24 – as well as being Editor at Large for Design Milk. She is currently exploring the question ‘can craft save the world?’ through an emerging body of work that includes her fifth book, Wasted: When Trash Becomes Treasure (Ludion, 2020), and a podcast, Circular with Katie Treggiden.

You can follow Katie Treggiden on Twitter, Instagram, and Linkedin. Read all of Katie Treggiden’s posts.